Digging into the Mars-Kellanova deal (Part II)

Breaking down the fine print: regulatory hurdles, risk allocation and the battle for control.

In Part I of our deep dive into the Mars-Kellanova transaction, we unpacked the timeline and key issues of the the biggest packaged foods transaction in nearly a decade.

Today, in Part II, we dig into the merger agreement itself where, in a brisk 80 pages excluding the schedules and exhibits, legal counsels Kirkland & Ellis and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and Affiliates (yes, that’s a mouthful - or, “Skadden” as they are commonly referred to) detail the terms of the deal, the conditions for closing, the outs, how risks are shared, how rewards are protected and how each side plans for the unknown. It’s also where creative deal structuring emerges, particularly for complex transactions with regulatory scrutiny, interlopers, and competing incentives.

The agreement that emerged from those intense August negotiations tells us as much about each side's priorities and concerns as any board presentation. There’s too much for this amateur to cover but let’s dissect how Mars and Kellanova's teams solved the puzzle of combining two food giants under intense regulatory scrutiny.

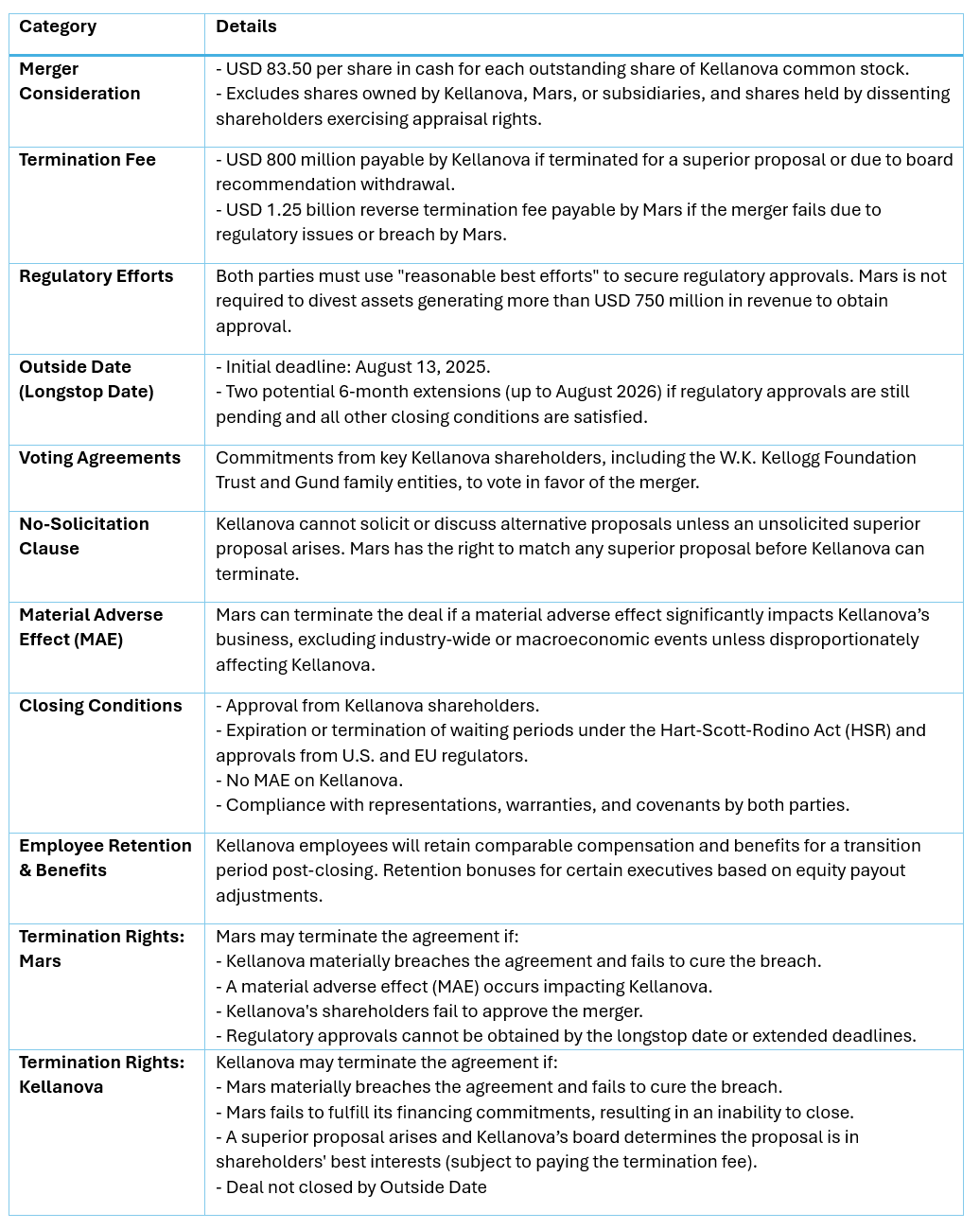

High Level Terms

We touched on the deal terms in Part I, but below is a quick summary of where the two sides landed.

How they got there

We of course do not have direct insights into the evolution of the negotiations, but we can piece together the key sticking points from the exchanges of drafts referenced in the background section of the merger agreement.

Below is a schematic of the evolution of the key of the terms as the two sides exchanged drafts over an intense three-week period that highlights the key sticking points, such as the ticking fee as one of the last points to be dropped, and the less contentious ones like the voting agreement.

Voting Agreements: locking up key shareholders

One key defensive parts of the deal is the voting agreements from Kellanova’s key shareholders: the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Trust (originally established by by cereal pioneer Will Keith (W.K.) Kellogg) and members of the Gund Family (early investors in Kellogg’s) owning 14.8% and 5.9% of the shares of Kellanova, respectively. The voting agreements bind each of them to vote all of their shares in favor of approving the merger as well as prohibiting them from supporting competing bids or proposals that could impede the deal with Mars.

The voting agreements thus locked-up Kellanova’s arguably two most influential shareholders and 21% of the shares, making it much harder for an interloper to succeed even if the offer was deemed to be a “Superior Proposal” by the board.

Keeping a tight leash on potential interlopers

In addition to the voting agreements, Mars bolstered its protections by adding robust and extensive no-solicitation provisions that had Kellanova and its advisors halt any discussions with third parties, barred them from soliciting any competing bids and even had them request the return or destruction of any confidential information sent to any other potential other bidders as far back as 2021!

While Kellanova board had the right to accept a superior unsolicited deal, Mars was not going to make that easy. Any unsolicited interest would need to be promptly relayed to Mars including the identity of the interested party, any requests for information and a description of the material terms of such “Company Takeover Proposal.” What constituted a Company Takeover Proposal had a relatively low barrier of just 20% of Kellanova’s outstanding shares, assets or revenue, rather than a full acquisition.

Anti-trust: Performance standards and a burdensome conditions

With regulatory approval being one of the critical hurdles to closing, the subject was heavily negotiated in the merger agreement. As we noted above, Mars fought hard to have sole control on regulatory-related decisions and strategy. This included having control over the communications and filings with the various regulatory bodies, as well - importantly - control over the sale process of any divestitures required required to win approval.

Reasonable Best Efforts

It takes a village to close a transaction of this complexity and the merger agreement goes into exhaustive detail to capture all the actions the parties need to “promptly”, or “as soon as practicable” or “as reasonably practicable”, do or not do to obtain regulatory approval, while of course cooperating, consulting, and notifying each other, as required by the agreement.

All these actions are prefaced with using “reasonable best efforts.” What that actually means (especially as it is not defined) has been oft debated and litigated although some case law has leaned to defining “reasonable best efforts” (and its cousin “commercially reasonable efforts”) as “impos[ing] obligations to take all reasonable steps to solve problems.”

Importantly, the merger agreement is consistent: the term is used 21 times and there are no other variations that could create the semblance of a hierarchy in meaning. It is qualified only once, to highlight that it could not be used to force Mars to accept financing terms materially worse than what the banks had initially committed1.

While this seems like a minor, it had serious implications in the failed Kroger-Albertsons merger where all the antitrust-related performance obligations were held to a “reasonable best efforts” standard, except for the clause relating specifically to Kroger’s obligations, which were held to the stronger “best efforts” standard. A small but significant distinction—which Albertsons (and owners Cerberus Capital) are hanging their hat on in a lawsuit seeking major damages for breach of contract and failure to exercise “best efforts” and to take “any and all actions” to secure regulatory approval.

The Burdensome Condition

One of conditions to closing in the agreement is that there is no “Burdensome Condition” on Mars to obtain regulatory approvals, which is defined as anything that has to do with Mars’ existing business (i.e. they can’t be required to sell any of their businesses without their consent) and any divestiture of Kellanova assets totaling revenues of more than USD 750 million. Mars can waive this condition, but it is up to them. Nevertheless, the pressure is still on Mars as any failure to close by the outside date because of a failure to obtain regulatory approval would require them to pay the USD 1.25 billion Reverse Termination Fee.

The USD 750 million threshold (pushed up from USD 500 by Kellanova during negotiations) represents less than 6% of Kellanova’s USD 13 billion in revenue in 2023, but the threshold is meaningful in that it covers four of Kellanova’s five largest brands. Given the concentration of the portfolio, there are few whole businesses that could be a “forced” sale.

Closing Conditions: really just one, anti-trust

The merger agreement does not contain any financing-related conditions although it did require Mars to undertake to obtain financing for it, which Mars did through a USD 29,000,000,000 (!!) bridge loan facility from J.P. Morgan and Citi.

The three main closing conditions are:

Approval by the Kellanova shareholders: received on November 1st, 2024.

No Material Adverse Effect (MAE): Absence of any significant deterioration in Kellanova’s business or external events disproportionately impacting the company (and subject to a lot of customary carveouts).

Regulatory approvals: the deal will require the approval of a host competition authorities. In addition to the FTC and European Commission, it’s likely authorities in the UK, Canada, China, India and Australia will also review the transaction.

Shareholder approval was of course a must (but limited risk barring a competing bid and supported by the voting agreements) and the heavily negotiated MAE clause is largely out of their hands, making regulatory approvals the biggest risk to the transaction. As of February 7th, 2025, neither the FTC nor the EC had yet to approve the merger, although the exit of FTC Commissioner Lina Khan following the arrival of the Trump administration may have brought some relief to the anxiety of both sides.

The Road Ahead

With shareholder approval secured and financing locked in, the final and most significant hurdle remains: regulatory clearance. The Mars-Kellanova merger is the largest packaged food transaction in nearly a decade, and while both sides meticulously crafted their agreement to navigate antitrust scrutiny, the regulatory environment remains unpredictable.

For now, both companies wait, the legal teams keep billing, filings are prepared, and lobbying has surely intensified behind the scenes.

Stay tuned for Part III where we will dive in to the fairness opinions of Kellanova’s financial advisors Goldman Sachs and Lazard where a lot of deal details and market information (and the fees) are often buried.

Update: continue with Part III here.

The proviso states, “in no event shall the “reasonable best efforts” of Parent, Acquiror or any of their Subsidiaries be deemed or construed to require, Parent, Acquiror or any such Subsidiary to seek or accept such alternative financing on terms materially less favorable in the aggregate than the terms and conditions described in the Debt Financing Commitment Letter (including the exercise of “market flex” provisions) as in effect on the date of this Agreement, as determined in the reasonable judgment of Acquiror.”